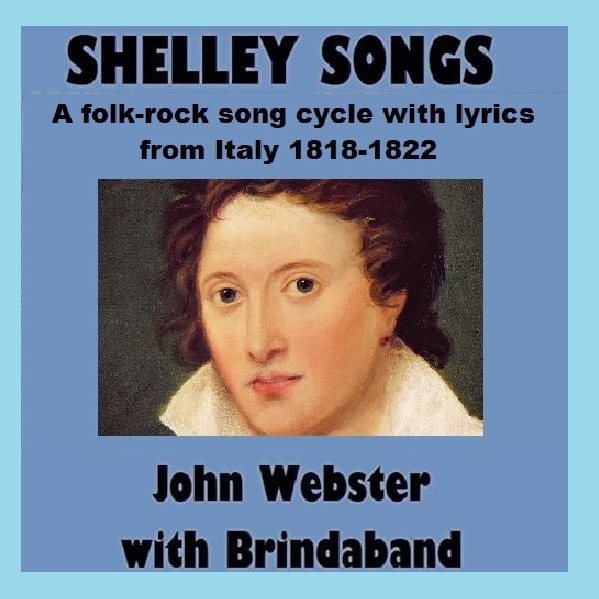

Songs that draw on around

two dozen Shelley poems and give access

to the poet’s empowering lyrical genius.

Click cover to download

Streaming now - listen on Spotify

With a major reassessment of Shelley taking place around

the 200th anniversary of his death (8th July 1822), and with

figures such as Benjamin Zephaniah and Ben Okri trumpeting

his role as a supporter of political and personal freedom,

‘Shelley Songs’ is a timely and valuable contribution to

the developing interest in the poet, providing an

easygoing encounter with his work.

So what's he all about?

Not only a poet, translator, essayist, but a radical democrat in his time,

the poet still fascinates with the modernity of his thinking:

'The quantity of nutritious vegetable matter consumed in

fattening the carcase of an ox could afford ten times the sustenance ...

if gathered immediately from the bosom of the earth.'

''A political or religious system may burn and imprison

those who investigate their principles; but it is

an invariable sign of their falsehood and hollowness'

'Hope, as Coleridge says, is a solemn duty

we owe alike to ourselves and to the world'.

Track listing:

Many a Green Isle

Rise like Lions

Wild Spirit

The World’s Great Age

Spirit of Delight

Heart of Hearts

Immortal Deity

Paradise of Exiles

The Pine Forest

The Triumph of Life

To Jane

The Funeral

Adonais

Many a Green Isle

Sources: Lines written in the Euganean Hills

Stanzas written in dejection, near Naples, Hellas

Many a green isle needs must be

In the deep wide sea of misery

Or the mariner worn, and wan

Never thus could voyage on

Day and night, and night and day

Drifting on his dreary way

Alas I have nor hope nor health

Nor peace within, nor calm around

Nor that content surpassing wealth

The sage in meditation found

And walked with inward glory crowned

Yet were life a charnel where

Hope lay coffined with despair

Yet were truth a sacred lie

Love were lust, if liberty

Lent not life its soul of light

Hope its iris of delight

Truth its prophets robe to wear

Love its power to give and bear

Many a green isle needs must be

In the deep wide sea of misery

Or the mariner worn, and wan

Never thus could voyage on.

Shelley’s years in Italy were marked by personal tragedy,

and the main chorus of this song was written in Este near Venice, some months

after his arrival in March 1818. The death of his young daughter Clara in Venice

had left him and Mary shattered. The Euganean hills

(depicted - with its 'green isles' - above)

would suggest a metaphor of consolation.

The lines written in Naples were also written

at a time of some personal difficulty, which scholars have not been able to fathom

although it may be connected with his mysterious `Neapolitan charge’.

But the final lines from Hellas reveal Shelley’s recourse to secular redemptive ideals

based on liberty; he would not agree that a decline in orthodox religious beliefs

would necessarily lead to social or moral decline.

Sources: Song to the Men of England,

The Mask of Anarchy

People of England wherefore plough

For the Lords who lay ye low ?

Wherefore weave with toil and care

The rich robes your tyrants wear?

The seeds ye sow another reaps

The wealth ye find, another heaps

The robes ye weave another wears

The arms ye forge another bears

Wherefore feed and clothe and save

From the cradle to the grave

These ungrateful drones who would

Drain your sweat, nay drink your blood

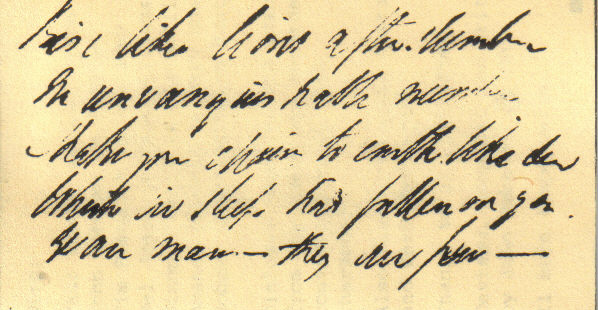

Rise like lions after slumber

In unvanquishable number

Shake your chains to earth like dew

Which in sleep had fallen on you

Ye are many they are few.

Ye are many they are few.

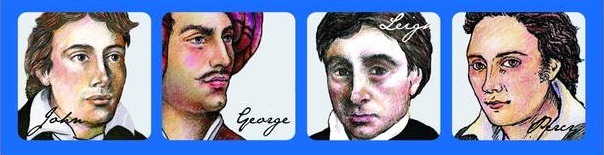

The political situation in Shelley's time was one of deadlock,

with the landowning classes monopolising political power and

fearful that the slightest reform would usher in violent revolution

on the French model. Changing social patterns, with Britain moving from a

predominantly agricultural society to an urban industrialising order,

meant that there was a new and increasingly literate –

but entirely disenfranchised – urban population.

sees him trying to bond popular energies into a united force.

As the Chartist Circular of 19th October 1839 put it: 'He wrote to teach his

injured countrymen the great laws of union, and the strength of the passive resistance'.

Shelley sent The Mask of Anarchy to his editor friend Leigh Hunt

but he did not publish it until after the Great Reform Bill in 1832.

Shelley's other post-Peterloo lyrics, which included his 'Song to the Men of England',

were not published during his lifetime. They had to wait till 1839,

when Mary published an (almost) complete edition of his work.

Wild Spirit

(A storm gathers over Florence)

Source: the Ode to the West Wind

Wild spirit, which art moving everywhere

Destroyer and Preserver, hear O hear!

A heavy weight of hours has chained and bowed

One too like thee: tameless and swift and proud.

O wild West Wind, thou breath of autumn's being

The leaves are driven, like ghosts from an enchanter fleeing

Scatter as from an unextinguished hearth

Ashes and sparks, my words amongst mankind!

Wild spirit, which art moving everywhere

Destroyer and Preserver, hear O hear!

Scatter as from an unextinguished hearth

Ashes and sparks, my words amongst mankind!

The World's Great Age

Sources: Hellas Prometheus Unbound, Act III; The Question

Prose: Lines written among the Euganean Hills

The world's great age begins anew

The golden years return;

The earth doth like a snake renew

Her winter weeds outworn.

Heaven smiles, and faiths and Empires gleam;

Like wrecks of a dissolving dream.

The loathsome mask has fallen;

The man remains

King over himself

Free from guilt and pain.

Women frank and beautiful and kind;

Looking emotions once they feared to feel

Speaking the wisdom once they dared not speak

Changed to all which once they dared not be.

I dreamed that as I wandered by the way

Bare winter suddenly was changed to spring.

Let the tyrant rule the desert he has made

Let the free possess the paradise they claim

Where all should live as equals and as friends;

And the world grow young again.

The world's great age begins anew

The golden years return;

The earth doth like a snake renew

Her winter weeds outworn.

This song gathers together Shelley's utopian verses from a variety of sources.

Matthew Arnold derided Shelley as an ‘ineffectual angel’

but modern historians have shown how his visionary verses made a significant

contribution to the attainment of universal suffrage in Britain

through their influence on key groups like the Chartists and the Suffragettes.

Part of his response to Peterloo was to offer an utopian and forward-looking

agenda, particularly in the last Act of Prometheus Unbound which he also completed in Florence.

He understood the value of a vision, but saw its achievement as subject

to 'the difficult and unbending realities of actual life'. As he put it to Leigh Hunt

in the dark days after the Peterloo massacre: 'You know my principles

incite me to take all the good I can get in politics, for ever aspiring to something more.

I am one of those whom nothing will fully satisfy, but who is ready to be

partially satisfied by all that is practicable'.

Spirit of Delight

Source: From an (untitled) Song

Rarely, rarely comest thou Spirit of Delight!

Wherefore hast thou left me now

Many a day and night?

Spirit false thou hast forgot

All but those who need thee not.

I love all thou lovest Spirit of delight !

The fresh earth in new leaves dressed

And the starry night Autumn evening and the morn

When the golden mists are born.

I love Love - though he has wings

And like light can flee,

But above all other things Spirit I love thee –

Thou art love and life ! oh come

Make once more my heart thy home.

This lyric is about being in what Shelley called being in an 'interval of inspiration'.

Yet it reminds you of the existence of a 'spirit of delight' and its importance,

and so achieves a positive emotional effect. 'Spirit of Delight' adds in the

introspective side of Shelley's work and shows how he examined emotional states.

It's edited down from eight verses to three, with verse one finishing with two lines from verse two.

Heart of Hearts

Sources: Dante's sonnet for Guido Cavalcanti (translated by PBS),

Epipsychidion, Lines for Emilia Viviani

Ah, my song; I fear but few

Fitly shall conceive thy reasoning

Of such hard matter doth thou entertain...

Amongst enchanted islands of sunlit lawn

In the clear golden prime of my youth's dawn

There was a being who my spirit oft

Met on its visioned wanderings far aloft

As one sandalled with plumes of fire

I sprang towards the lodestar of my desire

In many mortal forms I rashly sought

The shadow of that idol of my thought

I never was attached to that great sect

Whose doctrine is that each one should select

Out of the crowd a mistress or a friend

And all the rest to oblivion commend

There was a being who my spirit oft

Met on its visioned wanderings far aloft

Amongst enchanted islands of sunlit lawn

In the clear golden prime of my youth's dawn

The clear brow, the amorous lips

The eyes where past time reposes

These are images, images of her

The fragrance, yet still I seek the roses

Henry Salt, author of Shelley: poet and pioneer, called Epipsychidion

'the despair of the critics' and it doesn't have the cohesion of Shelley's greatest work:

it blends courtly love, autobiography, sexual and platonic passion and a philosophy of love.

I would defend Epipsychidion though on the grounds that it fulfils the old maxim:

'Know yourself'. Shelley wrote to a friend shortly before his death that he could not

now bring himself to look at it, but that 'it will tell you something' about 'what I am and have been'.

'I think one is always in love with something or another', he added;

'the error, and I confess it is not easy for spirits cased in flesh and blood to avoid it,

consists in seeking in a mortal image the likeness of what is perhaps eternal'.

In the early 19th century divorce was virtually impossible and Shelley was

expected to 'marry well' for the sake of the family fortunes; his father told him

he would provide for as many illegitimate children as he cared to father

but would never forgive a 'misalliance'. Husbands had complete control

over any financial assets the wife brought to the marriage, and women

who had sexual relationships before or outside marriage were written off as fallen women.

At a dance in Horsham Shelley had deliberately danced with a girl so regarded.

Shelley's championing of free love was really a plea that people should be free to

realise themselves in this life with who they loved, rather than be stifled by law and convention.

Virginia Woolf wrote: 'Shelley, both as son and as husband, fought for reason and freedom

in private life, and his experiments, disastrous as they were in many ways,

have helped us to greater sincerity and happiness in our own conflicts'.

Immortal Deity

Sources: Queen Mab (adapted from notes)

The Defence of Poetry; Immortal Deity.

There is no God;

Or rather, there is no creative God.

The hypothesis of a pervading spirit,

Co-eternal with the universe

Remains unshaken.

This power arises from within:

Poetry redeems from decay

The visitations of the divinity in man.

Oh thou immortal deity

Whose throne is in the depth of human thought

I do adjure thy power and thee;

By all that man may be, by all that he is not

By all that he has been and yet must be !

An important part of Shelley's life, work and career is the challenge

he threw out to conventional religious orthodoxy.

up a gauntlet, in defiance of injustice' he told Trelawny. Though he respected

Jesus of Nazareth as a teacher and moralist, he rejected the mythological element

and the Pauline superstructure of orthodox Christianity. Nor did he believe in

what he calls here a 'creative god', i.e. a protective, caring/angry paternal god;

he was consistent in attacking this Judeo-Christian model. The result was that

he looked elsewhere for sources of morality - substituting what he regarded as

innate qualities of benevolence and love of justice and liberty that were inherent in people.

This song with lyrics from Queen Mab, A Defence of Poetry and a fragment from his later years in Ialy,

expresses a tentative sense of a spirituality bound up with human potential –

'what men call God' being a kind of spirit of wisdom/justice/liberty/creativity/poetry

that can visit anyone.The line referring to 'the hypothesis of a pervading spirit, co-eternal with the universe'

may have been a reference to Sir William Jones's description of Indian Vedantic philosophy.

His earlier poem 'Hymn to Intellectual Beauty' ploughs the same furrow as this.

Shelley took the phrase 'Intellectual Beauty' from Mary Wollstonecraft who had written that

women were primarily valued for their 'soft bewitching beauty' – actually, she wrote,

there is something called 'intellectual beauty' as well. The 'Hymn to Intellectual beauty'

refers to a time in boyhood when, as Shelley put it, 'thy shadow fell on me'; he added:

'I vowed that I would dedicate my powers To thee and thine – have I not kept the vow?'

Paradise of Exiles

Sources: The Boat on the Serchio, Julian and Maddalo

Prose: Fragment on Beauty, Hellas, Prometheus Unbound ms. fragment, Adonais

Day has awakened all things that be;

The lark and the thrush and the swallow free;

The stars burn out in the clear blue air

The thin white moon lies withering there.

Thou paradise of exiles, Italy !

A heron comes sailing over me

Worlds on worlds are rolling ever

From creation to decay;

Like the bubbles on a river

Sparkling, bursting, borne away

Green and azure wanderer

Happy globe of land and air

The One remains, the many change and pass

Life, like a dome of many coloured glass

Stains the white radiance of eternity

This song consists of lines from Shelley's final years in Italy,

almost all composed in or around Pisa.

One of his boating expeditions during the summer of 1821

is described in 'The Boat on the Serchio'. The famous 'line paradise of exiles'

comes from Julian and Maddalo,written two years previously in Venice;

the line about the heron comes from

a piece of prose written during another of Shelley's boat trips.

The lines on the earth – 'green and azure wanderer' – owe

something to his fluency in Greek: the Greeks called

the planets 'wanderers' – the vagabonds of the solar system..

The Pine Forest

Sources: The Indian Serenade; The Pine Forest of the Cascine near Pisa;

When the lamp is shattered; To Jane: The Recollection

I arise from dreams of thee

In the first sweet sleep of night;

When the winds are breathing low

And the stars are shining bright;

I arise from dreams of thee

And a spirit in my feet

Has led me who knows how ?

To thy chamber window, Sweet!

We wandered to the pine forest

That skirts the ocean's foam

The lightest wind was in its nest

The tempest in its home

How calm it was, the silence there

By such a chain was bound

That even the busy woodpecker

Made (it) stiller by its sound.

Love's passions will rock thee

Like the storms rock the ravens on high

Bright reason will mock thee

Like the sun from a wintry sky;

Though thou art ever fair and kind

The forests ever green,

Less oft is peace in Shelley's mind

Than calm in waters seen

The final two verses belong to the last months of Shelley's life;

Verse 1 was written in Florence in 1819.

The pine forest on the coast about 12 miles from Pisa - visible from the air when flying into Pisa -

was one of Shelley's writing haunts: verse two commemorates a still day in February 1822

when Shelley, Mary and Jane went walking there. The sea has receded a mile or two since Shelley's time.

The final verse begins with four lines from 'When the lamp is shattered'.

That late lyric begins unseen with a shining lamp, perhaps the radiance of a love relationship.

It indicates how sorrowful Shelley had become about love that the lamp

is shattered at the outset of the poem. Though the verse belongs to a dramatic fragment,

rather than being an overtly autobiographical poem,perhaps it reflected the emotional distance

that had entered his marriage to Mary, largely due to the loss of their children;

he seemed to be trying to recreate that emotional bond with other

women like Emilia Viviani or Jane Williams. This is what drives

his final love lyrics in Pisa and Lerici; the tone of regret in the final four lines hints at the difficulties.

The Triumph of Life

Shelley's last house, the Casa Magni in San Terenzo, Lerici

and the view from its balcony

From The Triumph of Life

Swift as a spirit

Hastening to his task

Of glory and of good;

The sun sprang forth

Rejoicing in his splendour.

Before me fled the night

Behind me rose the day,

The deep was at my feet

And heaven above my head

When a strange trance over my fancy grew

Which was not slumber

And then a vision on my brain was rolled ...

Methought I sate beside a public way

Thick strewn with summer dust

And a great stream of people there

Was hurrying to and fro

Numerous as gnats upon the evening gleam

Yet none seemed to know

Whither he went

Or whence he came

Or why he made one of the multitude

Struck to the heart by this sad pageantry

Then what is life I cried ......

This song amounts to a bit of creative editing – a poem of 544 lines

being edited down to about 14 ! It examines the difficulties of living

an ethically ideal existence, or achieving self knowledge, with the poem

maintaining that most, even Shelley's admired Plato, fall by the wayside –

betrayed by 'the mutiny within'.

In the poem Shelley meets the figure of Rousseau

who undertakes to explain the vision to him: it's interesting to compare

this with World War One poet Wilfred Owen's poem 'Strange Meeting'

which uses the same device and has much the same tone as The Triumph of Life.

Owen was highly influenced by Shelley's view of the role of the poet;

he was reading 'plenty of Shelley' just before his death.

To Jane

The keen stars were twinkling,

And the fair moon was rising among them,

Dear Jane.

The guitar was tinkling,

But the notes were not sweet till you sung them

Again.

The stars will awaken,

Though the moon sleep a full hour later

To-night;

No leaf will be shaken

Whilst the dews of your melody scatter

Delight.

Though the sound overpowers,

Sing again, with your dear voice revealing

A tone

Of some world far from ours,

Where music and moonlight and feeling

Are one.

From the very last weeks of Shelley's life, a recollection of

an evening on the balcony of the Casa Magni. From the same notebook

that contained Shelley's draft of The Triumph of Life, its mood has been described

as 'the desire for an impossible indefinite prolongation of fleeting intervals of

beauty and joy or regret for their passing'.

(Nora Crook, The Complete Poetry of Percy Bysshe Shelley Volume 7)

The Funeral

Lyrics by John Webster

The quarantine officers stopped me

And sent me back to the quay;

Nonetheless Shelley and Williams

Kept heading out to sea

I watched till they disappeared into the haze

Then went down to my cabin to sleep;

I was woken by thunder and lightning

Coming crashing down over the deep.

And when the storm had cleared away

I looked where their boat had last been

Then I scanned the entire horizon

But they were nowhere to be seen.

(Mary Shelley: 'With us it was stormy all day and we did not

at all suppose that they could put to sea ….

Next day it rained and was calm – the sky wept on their graves…')

Two weeks on I was cantering over

The Mediterranean sands;

Despair in the pit of my stomach

And sweat in the palms of my hands.

I was riding along for miles and for miles

I was brought up short when I saw;

The lifeless body of Shelley

Lying there on the shore.

I rode back to Lerici

And there told Mary and Jane

That Shelley and Ned had been taken from them

By the sea and the wind and the rain

Then I built an iron furnace

And carried it down to the shore

Prepared the cremation of Shelley

As a crowd gathered silent in awe.

The air seemed to quiver and glisten

Twixt the sea and the Apennine;

Over his burning body I poured

Frankincense, salt and wine.

'My dear Trelawny' said Byron

Breaking the funeral's spell;

'I knew that you were a pagan

But you're a pagan priest as well !'

But not till the evening was on us

Was his body consumed on the pyre

All was consumed, except for his heart

Which I snatched from out of the fire.

And Mary is left with his papers,

And a question; she wonders how long

It will take for the world to realise

What it lost in this bright child of song.

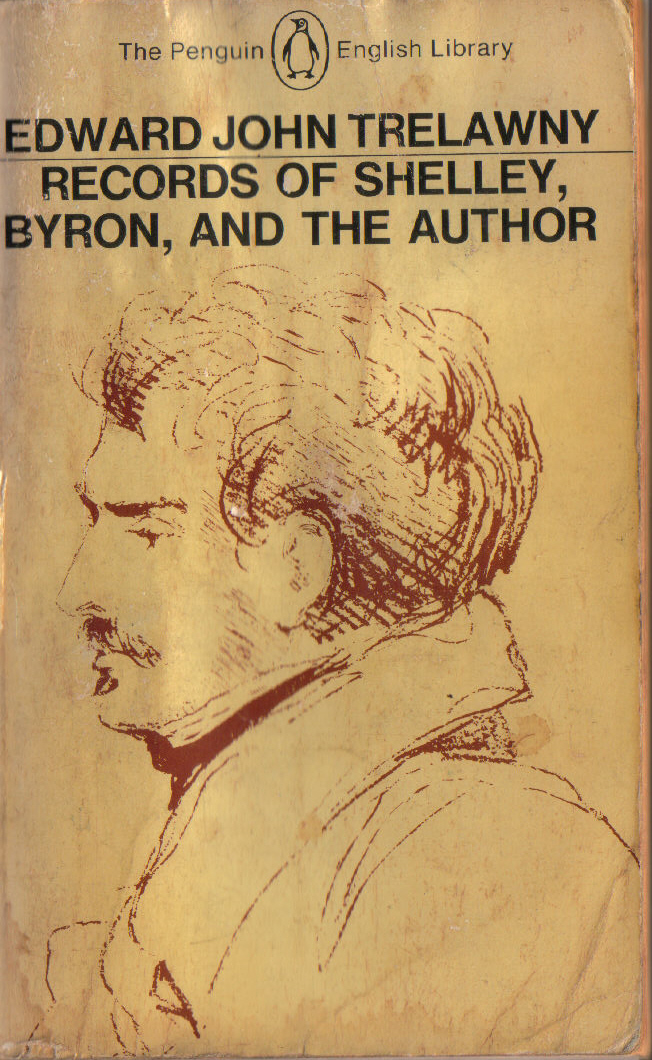

This song, sung by guest vocalist Keith Parker, is a precis in song of Edward Trelawny's

accounts of Shelley's death and his funeral on the beach near Viareggio in his book

'Records of Shelley, Byron and the author'. The Mary Shelley spoken piece

over the instrumental is taken from a letter she wrote to her friend Maria Gisborne

from Pisa as the funeral was taking place.

Adonais

Sources: To Stella (adapted from Plato's epigram translated by Shelley);

Adonais; the Ode to the West Wind

He was a morning star amongst the living;

Now that his spirit is fled;

He shines in the heavens like the evening star

He gives new splendour to the dead.

He hath awakened from the dream of life

He hath outsoared the shadow of our night;

The soul of Adonais, burning like a star

Beacons from the abode where the eternal are.

(The spring does not rebel against the winter - it succeeds it;

The dawn does not rebel against the night - it disperses it.)

The One remains, the many change and pass

Life, like a dome of many coloured glass,

Stains the white radiance of Eternity.

O wind if winter comes can spring be far behind?

Can Spring be far behind?

O wind if winter comes can spring be far behind?

Can Spring be far behind?

O wind if winter comes can spring be far behind?

Can Spring be far behind?

This song may be the first time that Plato (in verse 1) has ever been put to a backbeat!

(Or maybe, disappointingly,not, as scholars now think it belongs to a later era....)

It's sung by Ruth Murray, representing Mary Shelley paying tribute to her lost husband.

perhaps this life is nothing but a dream. The opening lines of Stanza 40 of Adonais

are followed by the two final lines of the poem. Adonais often comes to mind

when the young and gifted suffer an untimely death; examples could include

Brian Jones of the Rolling Stones (Mick Jagger read pieces from Adonais at the concert in Hyde Park),

River Phoenix, Kirsty MacColl, Stephen Lawrence, or John Lennon.

You could see Lennon in Shelleyan terms as an 'unacknowledged legislator'

who now 'shines in the heavens like the evening star'.

In his poem A Terre (Being the Philosophy of many soldiers)

Wilfred Owen referred to Adonais (see stanza 42):

'I shall be one with nature, herb and stone',

Shelley would tell me. Shelley would be stunned:

The dullest Tommy hugs that fancy now.

'Pushing up the daisies is their creed, you know'.

So Shelley's lyrics on death match today's largely agnostic attitudes

on the existence of the afterlife. What can continue after death

though is inspiration andstrength for those who remain.

The spoken fragment comes from Shelley's notebook from Lerici,

and is significant in that it repeats the central idea from the Ode to the West Wind.

In other words the grim vision from The Triumph of Life, written at the same time as the fragment,

is not (as some say) a final descent into pessimism on Shelley's part,

but part of a longer work in which sources for hope in a secular world

would - if he had lived - been explored.

The third verse is a reprise of the platonic verse from Paradise of exiles,

and the final chorus is from the last line of the Ode to the West Wind.

It brings out the link between the Ode to the West Wind and Adonais:

at the beginning of the final stanza Shelley wrote

'The breath whose might I have invoked in song/ Descends on me ….'

– a reference back to the west wind in Florence.

Shelley called death 'the great mystery' and once apparently, suggested

to Jane Williams, when they were in a little dinghy off the beach in Lerici,

that they 'solve the great mystery together'.

She replied 'no thank you I'd like my dinner first'!